Historian hosts talk on life before Buffer Zone

Published 7:00 am Thursday, May 15, 2014

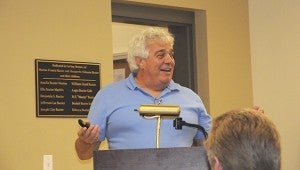

BEFORE THE BUFFER ZONE: Dr. Marco Giardino, a former NASA site historian, spoke at the Pearlington Branch of the Hancock County Library System Tuesday about the history of the towns before the Buffer Zone was created in the 1960s.

Photo by Alexandra Hedrick

The Pearlington Branch of the Hancock County Library System was packed Tuesday night with family members of former buffer zone residents wanting information on life in that area before 1961.

Former NASA site historian Dr. Marco Giardino spoke to the crowd about the history of the buffer zone site dating back to 12,000 BC all the way up to when NASA bought the 125,000 acre site in Hancock County in 1961.

Giardino said thanks to federal legislation that protects historical areas, NASA had a team of archeologists that would perform digs in certain parts of the buffer zone before construction took place.

During the digs, archeologists, including Giardino were able to identify prehistoric sites and uncover the structural history of the towns of Logtown, Gainesville and Napoleon.

The digs uncovered pottery, liquor bottles, bricks and other materials, some of it dating back hundreds of years, Giardino said.

Giardino gave a brief overview of the history of the area, which included occupation by the French and Spanish twice and by the English before becoming a United States territory and eventually a state in the 19th century.

He said historians and archeologists were able to trace the roots of settlements through land deeds and the records kept by NASA when they started purchasing land from the 660 owners for the buffer zone.

Through land deeds and diary entries, Giardino was able to trace the names of the first settlers along the Pearl River and how towns received their names.

One of the most prominent early settlers to the area, Jean Claude Favre, the father of Simon Favre, was sent by the French government to be a translator for the Choctaw Indians in 1767. Simon Favre is a well-known translator who was a resident in the late 1700s and early 1800s, Giardino said.

He said Jean Claude Favre owned large parcels of land and it is believed he transferred the land deeds in the area now known as Napoleon to his son when he died.

It is believed Simon Favre built the first structure in Napoleon, but land deeds show his father already had structures on his land in 1767, Giardino said.

He said an interesting fact about Simon Favre is that right before he died, he had eight deed claims and had purchased 800 empty barrels. Giardino said he always wondered what Simon Favre’s plans were for the barrels.

Another family that Giardino spoke about was the Koch family.

He said Christian Koch was a Danish merchant who settled in Bogue Houma in the 1830s, which historians learned because of Koch’s preserved diaries. Koch married his wife Annette Netto in the 1840s.

Koch had anti-slavery views and during the Civil War, confederate soldiers took him to Fort Pike. During his time at Fort Pike, Koch wrote detailed letters to his wife daily during the Civil War, Giardino said.

From these letters, historians are better able to understand the daily life of Civil War era residents in the area.

Through maps and deed drawings, archeologists were able to take those images and overlay them on modern satellite images of the area to discover areas of historic significance, Giardino said.

Despite maps, photos and drawings, Giardino said archeologists would never be able to uncover all of the historic evidence on the 125,000 acres.

“There’s never going to be enough archeologists and money to dig up what we want to dig up and the more you wait the more archeology you make,” Giardino said.

Giardino explained that archeologists dig three by three foot squares and may dig only ten in one summer.