Arboretum Paths: Nature’s lessons for landscaping

Published 5:17 pm Wednesday, July 27, 2016

Tough and easy to grow, purple coneflower is a native perennial attractive to butterflies and bees (Photo by Pat Drackett).

Last week, I attended the Cullowhee Native Plant Conference at Western Carolina University, which always pulls together a great group of native plant enthusiasts – nursery operators, botanists, horticulturists, designers, university professors and students, authors, native plant society members, and persons hailing from botanical gardens and arboretums. Celebrating its 33rd year, the purpose of the conference is to increase interest in and knowledge of propagating and preserving native southeastern plant species in the landscape.

The opening presentation was made by Thomas Rainer, a forward-thinking landscape architect from Washington, D.C., who spoke to a receptive audience about the need for learning how to intelligently design successful landscapes that will stand the test of time.

Thomas co-authored the 2015 Timber Press book with Claudia West, Planting in a Post-wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes, who was also a speaker at the conference.

Thomas referred to the litany of reasons that are typically used to convince someone about the merits of choosing native species.

While it is true that natives can be drought-tolerant, low-maintenance, and provide food for local wildlife, this “magic bullet” message is in need of updating.

Instead, he said, we need to focus on a different approach, such as learning more about where certain plants come from in order to better understand how to use them to create healthy, biodiverse landscapes.

Thomas presented some exciting projects, such “wild” areas being successfully designed within urban settings, and plant trials being conducted on native species. One of his statements that resonated was, “Nature’s technology is free and it’s waiting”.

A valuable lesson, he said, can be gained by observing the “weedy” plant communities growing between a sidewalk and curb.

In these inhospitable areas, highly diverse collections of plants exist, and thrive, despite stresses that include salt, pet urine, and lack of water. In other words, plants will grow just about anywhere!

The challenge is to learn which are the right ones for our particular site.

In Germany, designers are using the ecological preferences of certain North American perennial species as a basis for creating durable planting mixes, with colorful names such as ‘Silver Summer’, and ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’.

The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin, Texas is currently conducting research on a variety of systems composed of native plant species such as roof gardens for hot climates, lawn mixes, weed management, and plantings for Texas roadsides.

Our suburban landscapes, Thomas noted, generally contain only a small number of species, usually exotics from other continents. Consequently, this low biodiversity makes them of little use to local insects and wildlife.

We also rely too heavily on using mulch, he pointed out.

Learn to think of using plants as mulch – groundcover species – and not be afraid of planting closer together. Leaving large open spaces in landscape beds only creates areas that will need constant weeding.

Later, in her own presentation, Claudia West echoed that here in the U.S., we are not yet using groundcovers to their full potential.

At the conference, many attendees referred to the ground-breaking 2009 book by Dr. Doug Tallamy, “Bringing Nature Home”. An entomologist at University of Delaware, one of Dr. Tallamy’s main points is that insect-plant relationships are highly specific. If insects have not co-evolved with plants, they will not be able to eat them.

Over 95 % of terrestrial birds feed their young with insects, i.e. caterpillars. When landscapes are composed of “alien” species, less biomass is available to insects, which are eaten by wildlife.

Oak trees support over 500 species of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths). Exotic species may support only a few. Dr. Tallamy’s book provides lists of the plant families which attract the highest number of insect species. His message is simple– create more “wildlife corridors” (contiguous areas of plants that assist in wildlife movement and cover), reduce areas of lawn, and plant more native species!

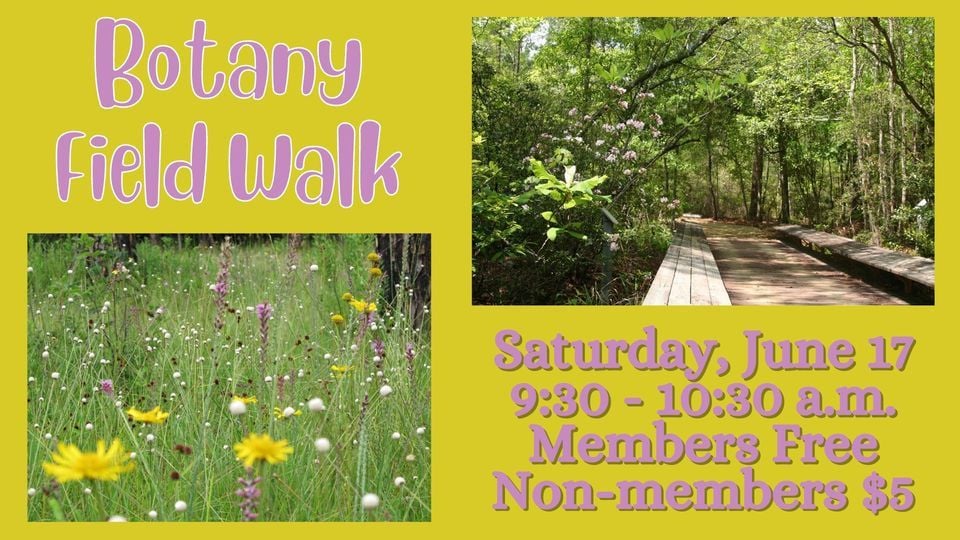

Mark your calendars for an exciting gardening program on “Coneflowers for the Home Garden” on Saturday, July 30, at 10:00 a.m. with Pearl River County Extension Agent Dr. Eddie Smith. Cost for non-members is $5.

For more information, see www.crosbyarboretum.msstate.edu. The Crosby Arboretum is located at I-59 Exit 4 and open Wednesday through Sunday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Patricia R. Drackett, Director and Assistant Extension Professor of Landscape Architecture

The Crosby Arboretum, Mississippi State University Extension Service